Duets: student and artist-mentor exchanges

One of the two main components of a student’s course of study in the MFA-VA program at Vermont College of Fine Arts is a semester-long studio project in which the student develops and/or challenges specific aspects of their art practice under the guidance of an Artist-Mentor.

The VCFA Artist-Mentor network is comprised of prominent contemporary artists who mentor students individually, during the semester. With over 1500 Artist-Mentors across the United States and Canada, VCFA students are ensured mentorship with a different Artist-Mentor each semester.

Student: Nadia Martinez (W 22)

Artist-Mentor: Doug Ashford

Ed. note: The following interview was conducted in November 2020 during Nadia’s 2nd semester in the VA Program – she is currently in her 3rd semester. Doug Ashford was Nadia Martinez’s 2nd semester artist-mentor. He is part of the founding faculty of the Visual Art Program at VCFA.

Nadia Martinez Last semester, I explored the idea of balance and imbalance as something we want to achieve as a society and on a personal level. My work focuses on the connections and relationships that we create with each other and our conditions, often reflecting on the things that are happening at the moment of its creation. Last semester, I thought it was appropriate to do that with the medium as well. I decided to change my approach and incorporate video to reflect on the virtual setting imposed by the pandemic. My main material was cotton.

Studio Project Title: Perfect Imbalance

Visual Culture Project Title: Beyond Language

Doug Ashford is a teacher, artist, and writer. He is Professor at The Cooper Union, where he has taught since 1989. His principal practice from 1982 to 1996 was as a member of the artists collaborative Group Material. A collection of his work, Writings and Interviews was published by Mousse Publishing and Grazer Kunstverein in 2013.

What is the structure of your exchanges?

N: I think we go with the flow pretty much. There is a little bit of a structure, because we do exchanges of emails and images and Doug has sent me a lot of things to read and names of artists to research. Sometimes when we meet, we actually start with whatever was shared.

D: With Nadia, in particular, I found it extremely both challenging and rewarding because her work was so developed in terms of the practical experiences that she had with the concept and material. But even more profoundly, the degree to which she was willing to take her practice to a particular place, which for many of us who are practicing artists, is a difficult thing to do. Any of us could throw the whole thing into a condition of questioning, and when we do that, it’s then difficult to work.

Part of the field of being an artist itself is to question the field. The dentist doesn’t go into his studio and say, “Hmm, what is a root canal and why am I doing it?” But the artist has to do that. And Nadia, in the most eloquent and careful method that I have run into for a very long time, will enter the structure of our relationship with those questions, “What am I doing and why am I doing it?” And that meant we were able to have an extremely open discussion from the very beginning.

Nadia, how have these discussions affected your thinking and process regarding your work?

N: It was very interesting because my Visual Culture investigation is language. All of a sudden, I’m trying to think where I draw a parallel between my Visual Culture work, what my desires or plans for my studio practice are, and also being able to comment on what is going on right now, because a lot of my work is about commenting on those issues. So, when I met Doug for the first time, I was electrified. He was putting so many ideas in front of me. I come from a sculptural background, mostly three-dimensional things, sculptural installations, and so how do I work right now?

Soon we were told we were going to have a virtual residency, so, sculpture now becomes more difficult. I had already done it once during the last virtual residency and knew how difficult it was to show sculpture. There was a lot of conversation between Doug and I in terms of what the object is, what are the meanings? Doug opened a whole new set of ideas to the things that I presented two weeks after our second meeting. I was also trying to think of how to integrate something that is more virtual and that’s when I sent him the first video I made.

And then everything changed after that.

D: That’s really important. The contingencies of the Pandemic are changing the concepts of how we think about materiality. At first, I think for lots of folks this seemed daunting, particularly for Nadia who is so skilled in the relationship to the histories of material applications to sculpture. For many artists the dilemma of what’s a sculpture online has produced a kind of paralysis.

But Nadia right away, immediately, seemed to be able to see into the conditions of what it means to do the labor of making. I don’t want to be overly optimistic about the conditions of the pandemic, but it has put us all – artists, educators, philosophers – into a place in which we have to reexamine the ethics of what we mean by production.

How have you been challenged this semester?

N: I was told that I was going to be challenged in a good way by one of Doug’s old students, so I was actually very excited about it. I think the more challenging thing in the beginning was, “Oh my god he is so smart, he is talking about so many things I don’t understand, how do I keep up!?” That was the first thing, and another is, I am very quick at turning things around and going back to my initial ideas – without being stubborn about it. And so, I was pretty much being constantly challenged every meeting that we had.

Doug has helped me open my horizons in directions I was not expecting. He mentioned Clarice Lispector, and to read her book, Água Viva. I kept imagining, visualizing things as I read. Her writing just becomes so physical, and they are only words. Água Viva really opened up a new window, a whole new way of thinking for me.

Doug had assigned me to make 100 videos and to email them to him. I thought, “Oh my gosh, that’s a lot!” I had never made videos before! But you know, you challenge me, and I will show up. After the 34th video, I believe, we met and Doug said, “I don’t think you need to make any more videos.”

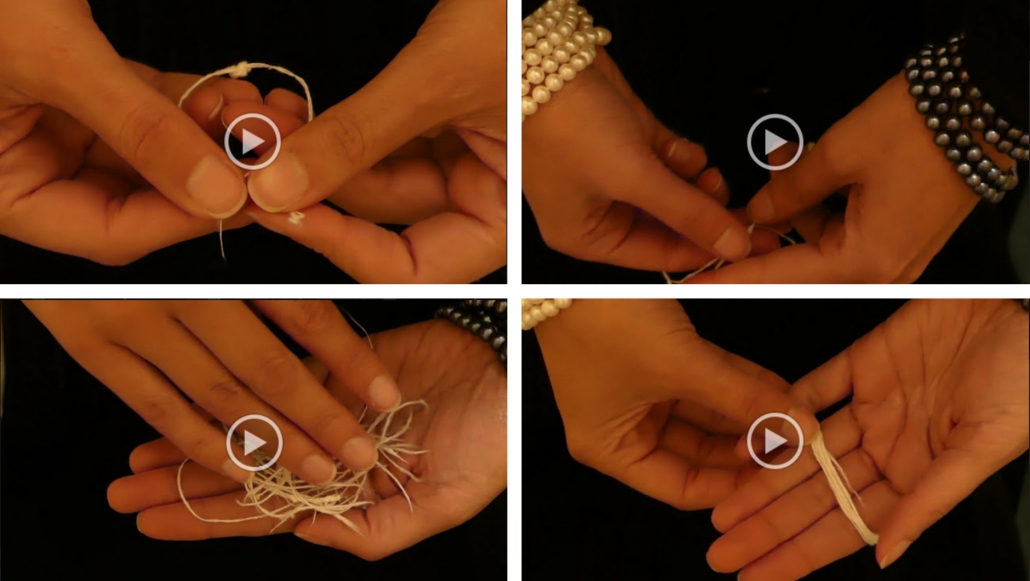

What I didn’t know was I actually needed the break from making videos because I was making at least two videos a day. I took two weeks to do research. Doug had mentioned Richard Serra’s videos, especially Hand Catching Lead, 1968. I have probably watched it twenty times now. That led me to Yvonne Rainer, the dancer that inspired Serra with her Hand Movie, 1966. Then I went into a spiral of research, consuming images, reading, and thinking, “Ok, I’m not making anything”, which was making me feel a little bit bad. I do have the need to make something with my hands, so little by little I was making things just to keep me occupied.

I was concerned because in the beginning I had said I wanted to use language this semester. But then at some point when I was making video, I thought I really don’t like my voice and I really didn’t want to add words to it, so how do I add language? He taught me that language did not need to be spelled out and that I could create language just by the images I was making.

I have also learned from him to check all spectrums, not just visual art, but literature, even science. I do get inspired by different things, but I think Doug showed me a different way of researching that I will be able to keep doing now.

How is it different from what your conception of research had been?

N: I think opening up my mind to possibilities for creativity, whether it’s science or literature or psychology, which we have spoken a lot about. How can that actually be implemented into my studio practice to create more interesting conversations? I realized that some of the points I was trying to make were shallow, they didn’t have a lot of roots, so a way of research that we have been talking about will allow me to create stronger roots.

Can you describe a pivotal moment that helped shift something for you?

N: I have always liked to be behind the scenes. I make my work and when I have an exhibition I am there, but I don’t really want to be there. I like the work to talk for itself. One of the most difficult things was to actually put myself in front of the camera. I went little by little. I felt safe to do the exercise of making 100 one-minute videos. Everything was an experiment. I saw it as a sketch book. It didn’t matter if I was there or not there. But little by little I was putting myself there. In some of them my whole body, in some of them just my hands.

Was this at Doug’s suggestion that you use yourself in the videos?

N: No. It was organic. That had been such a big thing for me because I’m just not comfortable to be “there”. But I became comfortable being there, maybe because I’m also working with the lighting and it’s all dark. That was definitely one of the moments of, “Oh wow, I actually can do this! I’m performing”. I didn’t know I would arrive at that – at least in this semester. So that was a big thing.

D: I really sympathized or tried to sympathize with the anxieties of the body in this case, but the capacity with which we have to identify a sense of understanding of each other through the physical nature of our bodies is embodied in the labor of the artist always.

I think Nadia’s body was always there, because of the amazing amount of skill and attention that she was able to train through the body into very complex sculptural and other forms of installation that would always create identifications with her physically. Nadia brought that reality, because of the history of her own practice, to me, so then I had to respond accordingly to say: your body was always there. I mean the depiction of the body is another issue, but the body was always there. For all the audiences, for all the shows she produced, years before she came to VCFA.

How has the VCFA Student – Artist-Mentor model informed the way you approach your process?

N: One thing for sure, I have never produced so much work in one year! That’s not true, but in the past, probably five years, to produce a body of work I would work, work, work for two months and I would be done pretty much. Now I think, “Where is all of this coming from?!” I’m writing, I’m working. I surprised myself. Mostly I tend to be a little rigid in how I approach my bodies of work. I don’t have a preconceived idea, but I have a plan, at least a goal.

But this time around, since I started at VCFA, I don’t. Because I say that I’m here to learn, I’m here to experiment, I’m here to make mistakes and I’m going with the flow. I do get frustrated every now and then. I’m making all this but where is the physical thing, where is the artwork? And so, my main thing has been to say, “Stop that thinking for a minute. You are making things and you will have something to show at the next residency”. Knowing myself, most likely I will. And as Doug was saying – ask questions – and play with it. Probably that’s the most important thing right now; I’m playing with the ideas. I haven’t been a student for a while, so I’m again allowing myself to play, which is wonderful.

What advice would you give a new student who is thinking about selecting an Artist-Mentor?

N: One thing is to find something that connects you with the person – something you admire. If I could find a video of the person talking, that was key for me. How are they communicating? Am I clicking with what they are saying?

I met my previous mentor, Nils Karsten, during a residency where he gave me a critique. I really enjoyed his critiques, they had substance and that was very important for me. At that time, I was thinking of the medium, even though the final work had nothing to do with what he did or what I used to do before.

I don’t think the medium is that important because during the time you work with that person so many things can change. In the beginning of this semester, I thought I was going to make sculptures and installations, and now, I am making videos. So, if I had selected somebody to work specifically in sculpture, I wouldn’t have been as open as I was to try something new.

There is a video of Doug reading a Nike commercial, and just by selecting that text, which I love actually, that already told me a lot about him. The way he was creating a dialogue through his artwork I found interesting – that was important to me. That was what I wanted to learn more about, more than the technique itself. At this point, being in a Masters program, I should know my craft. It’s more about how my thinking can develop.

D: It’s such a difficult proposition. Because as a teacher, and as someone who learned how to paint late in life, I would totally understand wanting a methodological response to the material conditions of making work. Yeah, we want to encourage everyone to become better at their field, but at the same time, we need to be able to see outside the field. We all know this as individuals, we have learned things about life and practice that come from completely different disciplinary and personal histories than we would normally expect.

It is also, I would like to argue, one of the beauties of the Visual Art Program at Vermont College, that it was founded, and has been able to maintain itself, as an educational context which does not fit into the recent very conservative reductive narratives of what education means. It’s not just repeating the ideas of technical and technocratic expertise that most other university programs have given in to.

N: One of the things I thought was interesting when I was about to end my last semester, it was suggested to me several times from different people, that I should work with certain artist-mentors based on their beliefs or interests. They thought I should write more about Feminism and I thought – well no, that’s not really my interest.

That was the part I was very jealous to keep; what was really important to me, front and center was who I wanted to work with. I’m not selecting anybody because they are this or that. I was looking for somebody with whom I could have a relationship for six months. I wanted to be able to communicate, to express my struggles and not be afraid of voicing myself, or even be excited too. Because that’s the other part, not to be ashamed that I am excited about something, even if it’s no good.

Rebecca Magill (W 21)

Rebecca Magill (W 21) Alumnx: Jo Ann Block (S 11)

Alumnx: Jo Ann Block (S 11)