We Cover the Waterfront:

conversations with VA alumnx, faculty and guests

Alumnx Profile: Kathy Couch (S 10)

For 17 years, Bessie Award winning designer Kathy Couch has been creating visual landscapes for performance and installation. Working in mediums of light and space, Couch has designed in traditional and non-traditional spaces both nationally and internationally. Since 2009, she has been working with the interdisciplinary collaborative a canary torsi.

Couch teaches Lighting Design at Amherst College and is a founding member and current president of the Northampton Community Arts Trust that seeks innovative ways to preserve space for imagination and creativity.

What draws you to working collaboratively versus a solo practice?

KC: I think about that a lot – there’s a variety of reasons why that is for me. Even in my personal life this notion of the autonomous, separated singular individual is very troubling to me – I think our sense of individualism is the root of many of our society’s ills. I have been casually researching these ideas for many, many years, just listening to and reading different things.

I once heard an interview with john a. powell in which he described the U.S.’s racial issues as rooted, obviously, in slavery, but also in the Enlightenment–this moment where the individual got held up as the whole truth of being. This notion of the separation between myself and the other is what allowed something like chattel slavery to occur in our country. Because I could see you as different than myself, I could create a little more distance, and all of a sudden you aren’t even a person. I could treat you differently and even brutally because ‘you’ no longer had anything to do with ‘me’.

I was really struck by the way this notion of holding up the importance of the individual has eroded our society’s capacity to take care and to make things together, in consideration of one another. It has allowed us to do a lot of harm to one another and to ignore the welfare of each other. To tend to each other feels like a struggle, an effort. Even to conceive of how to do that feels like something that is no longer ‘second nature’ to us.

But I seem to be wired to be drawn to these ideas that something that I make with another will be greater than simply the sum of the parts of those who are contributing. And that, in the working together and in the exchange, we get to places we can never get to alone. At the same time, I struggle with feeling very alone, and grapple with the resistance to give myself fully to another. I bump up against all of that societal training to not rely on other people, to think I have to figure it out on my own. It’s a lifelong quandary for me.

KC: You know I really believe in ‘the unity’, if you will, believe that we are all trying to get back to a place of alignment and connection with each other that is less fraught. But I also just struggle with it a ton, all the time. How do I get taken care of in these relationships? How do I trust that the concern for me is going to be held by the community? How do I hold onto taking care of myself, over taking care of somebody else? How do I negotiate all of that? And so, to me, this choice to almost always have my projects be collaborative in some way, is a choice to be in continual research of these questions.

Trying to understand how we navigate these relationships with each other is always fueled by this deep, deep belief, that something exists outside of all of us, something that we are all contributing to and are tied to–that is the greater thing. I get into trouble all the time about this: I am so disinterested in getting credit, or “oh that’s mine, I did that part”. And yet, the lack of recognition for my contribution results in me being denied access to certain conversations or participation because I am not seen as the sole genius who did this or that.

But I will probably always choose giving up something of myself–to contributing to some whole that I am working on with other people–over insisting on being singled out or individuated.

You are resisting through the choices you make about how you are going to work – resisting that impulse to be the individual with all of its negative connotations. That also has to be hard, the difficulty of losing yourself. The struggle of – where am I in this, not only with the credit, or the opportunities, but with your selfhood. You redefine what selfhood looks like. Always in relation, rather than not.

KC: Yes, I am endlessly grappling with the permanence of self and trying to assert that, and then trying to nail something down and articulate it. When I’m defined as a singular thing, I lose touch with all the other things that are possible, or that I could be, or am being, and all the other ways of being in relationship to other beings.

I really love what you said about selfhood – a different notion of selfhood. I have definitely thought of collaboration as a form, for lack of a better word. Collaboration as a medium, a form that you can practice and study. Not just a mode in which we sometimes do art, but that collaboration is an artform in itself.

It’s interesting, when I think about individualism and relationalism and interconnectedness, I don’t think I have ever gone so far as to say: no, actually I’m trying to redefine what it means to be a self. But I think that is what I am doing. I’m trying to be a different self than the one that is proposed to me by European, white culture. A self different than an individuated, autonomous being. I think I am trying to insist on a self that cannot be known without also knowing you and you and you. A self that exists only in relationship to everything else.

Could you reflect on One Body, the text you wrote for Last Audience – and your work with choreographer Yanira Castro and a canary torsi? [ed. note – Last Audience received two nominations for the 2020 Bessie Award: Outstanding Production and Outstanding Sound Design/Music Composition for Stephan Moore.]

KC: We developed Last Audience over the past couple of years and performed it as a live event in October at New York Live Arts. We were supposed to perform it this past spring at MCA Chicago as part of their performance art programming, but then the pandemic happened. Gratefully, instead of canceling our contract, Tara Aisha Willis (of the MCA) was able to work with Yanira Castro to procure a commission for us to create a version of Last Audience that could be experienced remotely. And so, that’s what we have spent the last 6 months doing–creating a performance manual.

The live performance was very much about enlisting the audience to be the performers to enact scores that we, as guides, would lead them through. Ultimately, they became the enactors of these scores in the space as a kind of ritual. We initially explored numerous structural ideas and elements from the requiem mass, thus a lot of Catholic notions got woven in, particularly around ideas of judgement and mercy.

KC: In adapting this piece into something that people could experience in their own homes, we decided to take those scores that we initially led the audience through in the live version and rewrite them as a set of performance manuals. These are now available to be purchased as a set and enacted in your own home in whatever way you wished. From the outset, the piece has explored questions of agency and resistance. How do we get people to take their agency? Is this even something that you can do? As performers, we were, at times, very confrontational, pushing at the audience somewhat in order to inspire forms of resistance. It was a very complicated piece because people would come out and say: I didn’t feel like you gave me agency. We realized, well, I can’t actually give you agency because if I tell you you have agency, then actually you aren’t an agent. As it has turned out, the manuals took another step towards people having agency (we hope), because they are in their homes and in their communities and they can choose to enact these scores in any way they might imagine.

In a way, these booklets are quite literally ‘instruction manuals’, very direct and insistent, but with quite a bit of poetry and openness to them. We hope they set a tone of deliberateness and intentionality, coupled with a freedom to do more of one’s own choosing. Yanira Castro and I rewrote/adapted the original performance scores and then created the booklets with a team of designers at the MCA. There are five booklets as part of this collection, each representing one of the five sections of the original live performance.

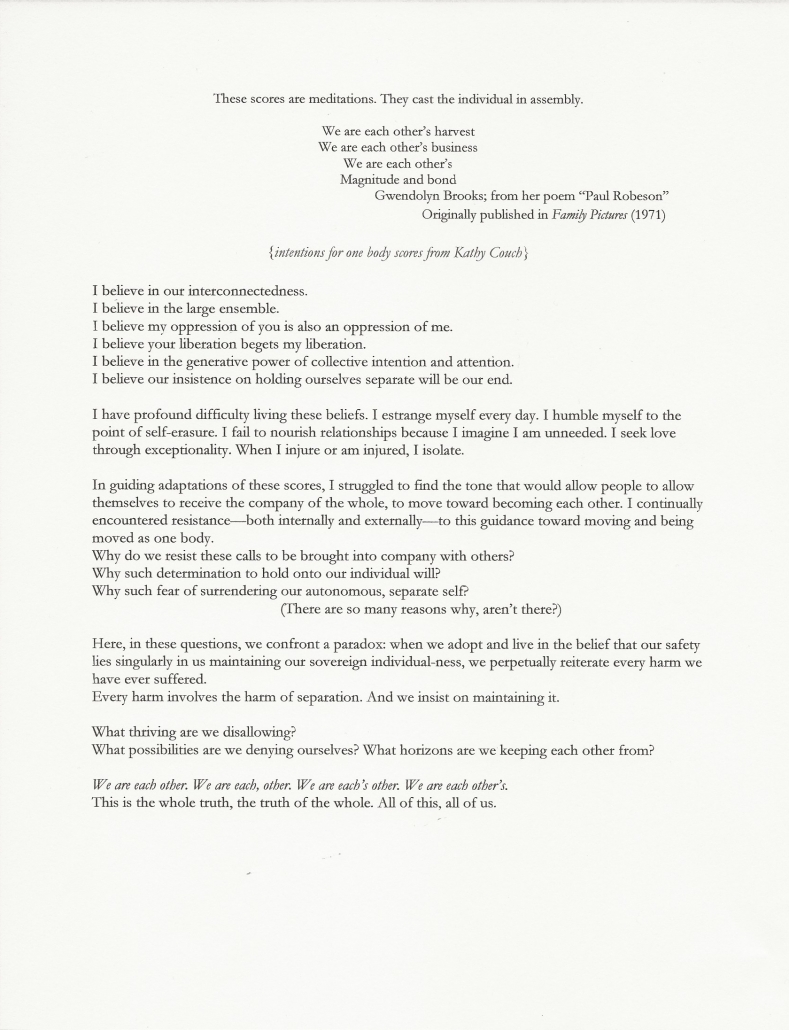

KC: In addition, we had performers who were part of the original creative team write an intention to serve as an introduction for each of the five booklets. I wrote a short essay of intention for the section entitled One Body. Each live performance began with one of the scores from One Body. They are scores that gather people together in a shared activity or a collective action. It was the only moment in the performance when everyone in the room was being directed through the same set of activities.

I wrote this introduction, this intention for One Body, about what is it to become one body and our resistance to doing so. Why do we resist things like instructions to bring us into unison with others or into collective activity with others? See, here I go again with these same questions of self and other…

As people begin to perform these scores at home, they are invited to contribute still images to a project website. These images serve as an index of their performance and become part of an online archive of this project as it happens around the world. Of course, I adore the way that this archive offers evidence of a kind of connectedness and belonging to something beyond our pandemically isolated selves.

KC: This question of how to feel my connection or my interconnectedness with others while I am isolated, quarantined, in lock down is something that has come up for me during the pandemic, and that I have explored in some other projects during this time. When I can’t be in the physical presence of others, can I lean into this capacity to connect across distance and maybe across time with people? Can I know that they are there?

We have seen notions of this come up with the uprising and the reckoning that’s going on around white supremacy and anti- black racism. It’s something that we have got to get better at: being able to have shared intention across distance and to be able to act in concert with each other even when we are not in the same place.

So, how can I trust that there are other people out there who are making things happen or caring about things I care about or sharing my intention enough that I feel like I have company to be able to take the risk, to take action on something that I feel is important and not feel like I’m the sole actor in doing so? I am curious about that – about our capacity to connect across distance.

KC: There are physicists who have measured these things: once you have two electrons vibrating near each other, having this resonant vibration, then even when they move to a great distance from one another, they still react, change, and respond in concert with one another.

It leads into this other project I have been doing during the pandemic, since April, with a musician friend Batya Sobel. In response to an invitation by my friend Melissa Morris and her composition this placement/displacement, we reimagined for this time of the quarantine and distancing — a recently-begun investigation of making sound together. One of our early recordings first appeared on her website.

We call our project bottle listening, or sometimes bottles, for short. In April, we began a daily practice of making sound with glass bottles – like blowing into a bottle, clinking them together, etc. We play at a chosen time each day but are sonically separated (she lives a couple of towns over and I am here at my house) so we can’t hear each other when we are playing. We warm up for 15 minutes and do a sort of tuning, taking inspiration from Pauline Oliveros and her notions of deep listening. Essentially, we try to tune into one another and try to hear one another across this distance. Then we play. As we play, we record ourselves in our space alone and then I take our recordings and put them together in a single track just to hear the duet that we had made that day.

KC: When we first started the project, we would play for the number of seconds equal to the number of total Covid deaths reported in Massachusetts as of that day. I think our first time playing together, we played for 756 seconds because there had been 756 deaths in Massachusetts. After some time, we changed it so that we now play for the number of total reported deaths for that day in Massachusetts. When we switched, Massachusetts was experiencing upwards of two hundred deaths every day.

We are still continuing the practice and we will play for 5 or 15 or 23 seconds, whatever it is for that day. Of course, recently, the daily death total has begun to greatly increase again, sometimes reaching 89 deaths a day. And throughout the project, we have only had one day with no reported deaths in Massachusetts.

What did you do then?

KC: We recorded silence.

It’s been an amazing practice and offered me much affirmation for this sense of connection. When you listen to the merged recordings it’s astounding sometimes how similar our tone or pacing will be or how we will fall into a kind of call and response kind of thing, even though we aren’t actually physically hearing the call to respond to. Again, it’s leaning into this notion of being connected to one another in ways that we don’t like to believe are possible, but obviously very much are.

Is there an end point?

KC: Yes, this is a question that has come up for me recently. Not only are we tuning into one another, but both Batya and I have a sense of tuning into the people who are dying, and then all of the people connected to all of those people. Pretty early on I started thinking of these recordings as little sonic memorials, and I started challenging myself to make a 5 or 15 second memorial, each moment filled with and connected to the spirit of another.

It has been very intense, feeling what’s going on in the state where I live, with the amount of loss and transitioning that people are experiencing, and feeling, in one small way, connected to that. And then trying to find a way to honor and attend to that daily. It was heavy at times. In the first couple of recordings, you can definitely hear that I am crying. Also, there is a certain balm in having that sensation of connectedness – you are present, and you are present with others – you are not in this little bubble of your own anxiety and fear.

We have been thinking about how to make the project accessible to others. I have had a vision of creating a website where people could listen to each of our duets. I feel that it would offer an entirely different way of experiencing the pandemic–one that translates data into physical sensation. And, also, creates a space for people to connect and offer their attention to others’ breath and loss and life. In a way, I suppose it would be a record of us continuing, together.

How do you respond to fallow periods or blocks?

A mentor/co-imaginer of mine, Gordon Thorne (artist and artist advocate), spoke often of the necessity of allowing things to lie fallow. We stewarded some art spaces together and he always insisted that we leave open time in our programing calendar so that the space could rest, could empty, could re-calibrate after all the artistic energy that had just occupied it.

It was certainly an analogy he took from land stewardship and I have since integrated it into my understanding of an artist’s life/process. These times of lower activity and less output are essential for the nourishing of our artistic spirit, for maintaining the fertility of our imaginations. So when I find myself in such a period, I lean into this understanding that fallowness fosters fertility and am less easily coerced into panic about producing or performing.

How have your experiences as a student at VCFA shaped your current practice?

In having to follow my ‘studio plan’ and do my research project while also maintaining a full-time job, I started to experience ‘being an artist’ as part of my ‘everyday’ life. I think the structure of the VCFA program insisted that I integrate my ‘artistic practice’ into the daily practice of living, such that they are now quite indistinguishable from one another. I don’t think I’ve appreciated the fullness of that until this moment of answering your question.

One other thing…one of my faculty advisors there really taught me the fruitfulness of offering my full attention to a single, specific thing; and how this close attentiveness opens the way to our larger, expansive understandings and imaginings.

What, or who, are you listening to, reading, watching, looking at?

Listening to: Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guébrou, Cymande, and the podcast “Phoebe Reads A Mystery”.

Reading: totally swept up this summer by the novels Days Without End and A Tale for the Time Being; writings by the women of Grafton Architects; M Archive; poetry by Mary Ruefle; essays of Audre Lorde; and New Yorker cartoons. And lots about being an anti-racist.

Watching: just like everyone else in lockdown, Schitt’$ Creek and The Great British Baking Show.

Looking at: well, not enough. But most recently allowed myself to be subsumed into Agnes Martin’s work again.

What three skills do you think are necessary for a human to navigate and participate in the world?

Here are some ‘skills’ that feel essential to my being human

- The ability to quiet myself so as to listen, deeply. To the things that are hard to hear. To the things that are barely audible. To the things beyond my aural range, and believe them perceptible.

- Knowing how to rest. We have a lot of work to do, together. The only way to keep going is to rest along the way.

- Allowing myself to be moved. We must hold ourselves open to being impacted, to being changed, to being effected (or do I mean ‘affected’?) 😉 In so doing, we commit to the truth of our interconnectedness.

The Kitchen Sink Project with Naomi Even-Aberle (W 19)

The Kitchen Sink Project with Naomi Even-Aberle (W 19)  Artists Against Fascism (AAF)

Artists Against Fascism (AAF)